Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

📖 Get lost in a tale that feels like silk against your soul!

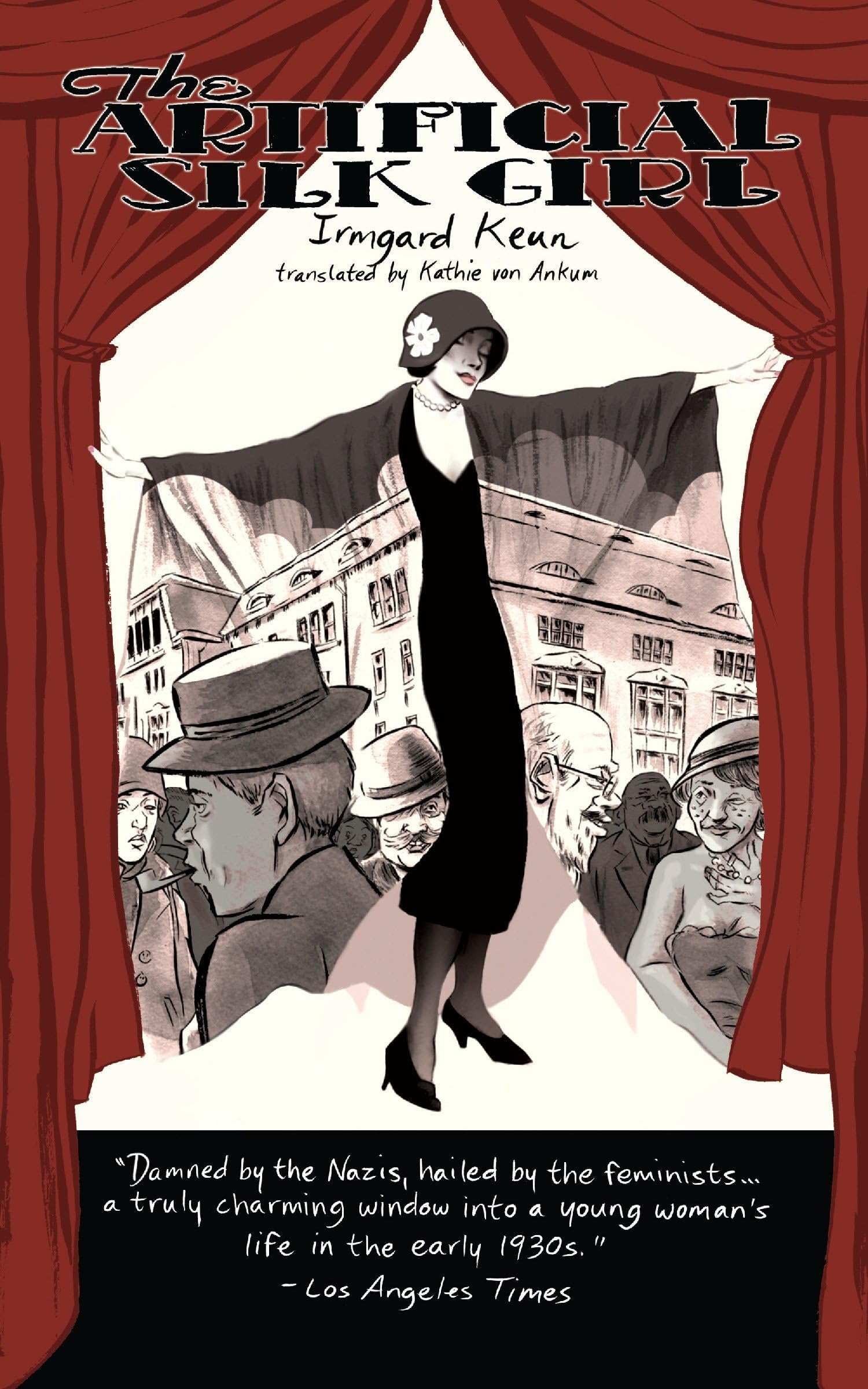

The Artificial Silk Girl is a used novel in good condition, offering readers a chance to explore a rich narrative filled with depth and elegance. Perfect for those who appreciate literature that resonates on multiple levels.

| Best Sellers Rank | #1,250,476 in Books ( See Top 100 in Books ) #1,852 in 20th Century Historical Fiction (Books) #6,777 in Classic Literature & Fiction #12,721 in Literary Fiction (Books) |

| Customer Reviews | 4.1 4.1 out of 5 stars (257) |

| Dimensions | 5.01 x 0.46 x 7.96 inches |

| Edition | Reprint |

| ISBN-10 | 1590514548 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1590514542 |

| Item Weight | 1.48 pounds |

| Language | English |

| Print length | 216 pages |

| Publication date | June 14, 2011 |

| Publisher | Other Press |

M**E

“The city isn’t good and the city isn’t happy and the city is sick, but you are good and I thank you.”

(4.5 stars) First published in Germany in 1932, when author Irmgard Keun was only twenty-two, The Artificial Silk Girl, a bestselling novel of its day, is said to be for pre-Nazi Germany what Anita Loos’s Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1925) is for Jazz Age America. Both novels capture the frantic spirit, the eat-drink-and-be-merry ambiance, and the materialism of young people like Doris – and Lorelei Lee in the Loos book – who haunt the urban clubs as they try to work their way into a lifestyle much grander and more vibrant than anything their mothers could ever have hoped for. Many attractive young women, regardless of their education and social experience, have set their hopes on becoming part of the privileged urban social scene, which they hope to achieve through the attentions of successful men with whom they flirt and seduce. In The Artificial Silk Girl, main character Doris starts out in a small city, where she wants to be an actress, while supporting herself as a stenographer and eventually writing a commentary about her life which author Irmgard Keun presents as Doris’s point of view. The authorities in Germany were not pleased, however, with Keun’s published depiction of Berlin life as Hitler and the Nazis, preparing to take power, envisioned it. Within a year, her books were confiscated and all known copies were destroyed. In 1936, Keun, firmly opposed to Nazism, escaped Germany for Belgium, Holland, and later New York. Doris, the “artificial silk girl,” has no politics, focusing almost completely on her own ambitions, and the novel that follows is both fun and very funny, based entirely on the persona of Doris – totally goal oriented, unafraid to take chances, willing to do anything to get what she wants, and very clever. Her voice – honest, bawdy, and surprisingly guileless – also shows her intelligence, and her pointed observations and insights into those around her give the author unlimited opportunities for unique descriptions: One restaurant is “a beer belly all lit up,” and dancing the tango “when you’re drunk…is like going down a slide.” Her feverish excitement at getting a small part in a show beguiles the reader, and when her outrageous behavior forces her to escape not only the theater but the city itself, the reader cannot help but root for her eventual success. Dividing the novel into three parts reflecting the seasons and the symbolism associated with them, the author creates a wild, spontaneous, free-for-all of action in Part I, which takes place at the end of summer. Part II begins in Late Fall in Berlin, a much larger city, and the reader expects that this will be a darker and probably more contemplative time. The gradual change of mood here increases the reader’s identification with Doris and her goals. Part III, “A Lot of Winter and a Waiting Room,” introduces three men, each of whom affects Doris’s life and future and helps bring about new recognitions by Doris and a realistic conclusion to the novel. The book’s timeless themes regarding women and how they see themselves, combine with history in a unique way, giving life to a less publicized period of history and new insights into the lives of some of the women who lived through it.

P**D

A female I am a Camera only more so

Evidently Anita loos’ Lorelei Lee the protagonist in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes begot a small industry in in variations on that character. Irmgard Keun’s The Artificial Silk Girl’s novel has Doris as a German version. Appling the term in a number of ways, Doris is a hot mess. She is immoral, but with something of a street morality, she is a victim of a male centered world, and in it something of a predator. Her dream is to be so famous and rich as to never need to do anything, but she expects it to happen, without her needing to work or do much more than simply wait for it to come to her. Ms. Keun writes well enough. Her character is so chaotic that we have to be able to follow the Doris’s first person narrative as she flitters among topics and shares outlandish but evocative observations. Technically this may be family friendly. For all the absents of adult vocabulary, the themes are adult. Sex being Doris’s only reliable means to her drifting ends. I suspect there are some fine academic papers about the possible contrasts and comparisons with books like Isherwood’s Berlin stories, or Joseph Roth’s What I Saw or even the Federico Fellini movie masterpiece “Le notti di Cabiria”, better known in America as Sweet Charity. Of these I think Doris is far more visual and therefore more of a “camera” than Isherwood’s outsider, academic narrator, and more of the people than Austrian reporter Roth. We meet Doris, in the inter war years of the Weimer Republish. We are introduced to her somewhere after the beginning of her story. She had been from small town Germany. She felt that her destiny was in Berlin, but that she could not get a start without something to mark her appearance. She steals a coat. This coat and the fact that it is stolen will become important to all her future decisions. She is now without papers and must be careful about anything that might have the official world become aware of her. With this new outer appearance, she runs away to Berlin. There her goal is to become rich and famous, but she has no concept of how that happens. People are mostly born it, and simply have money. Unlike the American Lorelei Lee, Doris is cold, critical and almost without scruple. She will lie and endanger others if it gives her a faint crack at being an actress, but does so without a larger plan. She willingly lets herself be a kept woman. But usually for men who are barely middle class and from the beginning cannot be depended upon to provide her with the diamonds that could insure her future. Mostly she drifts along on the fringes of Berlin. She quickly leans the city in terms of which bars are open late, where she can depend on others to buy her dinks and food, and maybe latch onto the next man to let her exchange her body for such hotel services as they can provide. She is very class conscious. Even extending the divisions into her place in her immediate social order. She is above the prostitutes that she lives among. Always reminding herself and the men who approached as one, that she is a lady. That she mostly survives by exchanging herself for loveless sex never lets her think of herself as a sex worker. What she is very good at is inventing various, often contradictory narratives, rationalizing her misbehavior and condemning others, mostly men. What make Doris interesting is her visual impressions. Here she is talking with a man who was blinded during WW I. He is not exactly a lover but they have what is for Doris a meaningful relationship. He asks her to describe her day before coming to visit with him: And he asks me: “Dear voice of a folk song, where did you go today?” “I was on Kurfurstendamm.” “What did you see?” And I must have seen lots of colors there: “I saw—men standing at corners selling perfume, without a coat and a pert face and a gray cap on—and posters with naked and rosy girls on them and nobody looking at them—a restaurant with more chrome than an operating room—they even have oysters there—and famous photographers with photos in showcases displaying enormous people without any beauty. And sometimes with.” A cockroach is crawling around—is it always the same one?—and there’s no air in the apartment—let’s smoke a cigarette— “What did you see?” “I saw—a man with a sign around his neck, ‘I will accept any work’ with ‘any’ underlined three times in red—and a spiteful mouth, the corners of which were drawn increasingly down—and when a woman gave him ten pfennigs, they were yellow and he rolled them on the pavement in which they were reflected because of the cinemas and nightclubs.” “What else do you see, what else?” “I see—swirling lights with lightbulbs right next to each other—women without veils with hair blown into their faces. That’s the new hairstyle—it’s called ‘windblown’—and the corners of their mouths are like actresses before they take on a big role and black furs and fancy gowns underneath—and shiny eyes—and they are either a black drama or a blonde cinema. Cinemas are primarily blonde—I’m moving right along with them my fur that is so gray and soft—and my feet are racing, my skin is turning pink, the air is chilly and the lights are hot—I’m looking, I’m looking—my eyes are expecting the impossible—I’m dying to eat something wonderful like a rumpsteak, brown and with white horseradish and pommes frites. Those are elongated homefries—and sometimes I love food so much that I just want to grab it with my hands and bite into it, and note have to eat with forks and knives—” “What else do you see, what else do you see?” “I see myself—mirrored in windows and when I do, I like the way I look back and then I look at men that look back at me—and black coats and dark blue and a lot of disdain in their faces—that’s so important—and I see—there’s the Memorial Church with turrets that look like oyster shells—I know how to eat oysters, very elegant—the sky is pink gold when it’s foggy out—it’s pushing me toward it—but you can’t get near it because of the cars—and in the middle of all this, there’s a red carpet, because there was one of those dumb weddings this afternoon—the Gloria Palast is shimmering—it’s a castle, a castle—but really it’s a movie theater and a café and Berlin W—the church is surrounded by black iron chains—and across the street from it is the Romanisches Café with long-haired men! And one night, I passed an evening with the intellectual elite, which means ‘selection,’ as every educated individuality knows from doing crossword puzzles. And we all form a circle. But really the Romanisches Café is unacceptable. And they all say: ‘My God, that dive with those degenerate literary types. We should stop going there.’ And then they all go there after all. It was very educational for me, and like learning a foreign language. And so this combinations of visuals observations, and metal impressions. Sentences can flow one form the next or not. Doris is a hot mess. She is not without insights and has something to tell an observant reader.

M**T

ABRIDGED Translation, not complete

WARNING -- this translation has been abridged, without either translator or editor acknowledging it. Chunks of the German original are simply omitted. Why is it legal to do this (it is certainly not ethical)? Someone ought to let the German publisher (DTV) or the estate of Keun know. If you want the entire book, go look for Basil Creighton's older translation. This translation is very readable and lively; pity it isn't complete.

N**S

Irmgard Keun’s ‘The Artificial Silk Girl’ limns of pre-war Berlin and is an account of the adventures of an archetypal material girl fashioned from the work of Anita Loos in ‘Gentlemen Prefer Blondes’. The novel was published in 1932 and soon banned by Nazis and Keun was forced to flee from Germany. With the advent of the Second Wave Feminist Movement in Germany in order to combat the gender disparities in post-war country, several works by women writers including The Artificial Silk Girl were rediscovered. "𝘐𝘧 𝘢 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘯𝘨 𝘸𝘰𝘮𝘢𝘯 𝘧𝘳𝘰𝘮 𝘮𝘰𝘯𝘦𝘺 𝘮𝘢𝘳𝘳𝘪𝘦𝘴 𝘢𝘯 𝘰𝘭𝘥 𝘮𝘢𝘯 𝘣𝘦𝘤𝘢𝘶𝘴𝘦 𝘰𝘧 𝘮𝘰𝘯𝘦𝘺 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘯𝘰𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘦𝘭𝘴𝘦 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘮𝘢𝘬𝘦𝘴 𝘭𝘰𝘷𝘦 𝘵𝘰 𝘩𝘪𝘮 𝘧𝘰𝘳 𝘩𝘰𝘶𝘳𝘴 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘩𝘢𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘱𝘪𝘰𝘶𝘴 𝘭𝘰𝘰𝘬 𝘰𝘯 𝘩𝘦𝘳 𝘧𝘢𝘤𝘦, 𝘴𝘩𝘦'𝘴 𝘤𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘦𝘥 𝘢 𝘎𝘦𝘳𝘮𝘢𝘯 𝘮𝘰𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘳 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘢 𝘥𝘦𝘤𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘸𝘰𝘮𝘢𝘯. 𝘐𝘧 𝘢 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘯𝘨 𝘸𝘰𝘮𝘢𝘯 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩𝘰𝘶𝘵 𝘮𝘰𝘯𝘦𝘺 𝘴𝘭𝘦𝘦𝘱𝘴 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘢 𝘮𝘢𝘯 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘯𝘰 𝘮𝘰𝘯𝘦𝘺 𝘣𝘦𝘤𝘢𝘶𝘴𝘦 𝘩𝘦 𝘩𝘢𝘴 𝘴𝘮𝘰𝘰𝘵𝘩 𝘴𝘬𝘪𝘯 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘴𝘩𝘦 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦𝘴 𝘩𝘪𝘮, 𝘴𝘩𝘦'𝘴 𝘢 𝘸𝘩𝘰𝘳𝘦 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘢 𝘣𝘪𝘵𝘤𝘩." The naivety of young Doris, the protagonist was ill placed in a country where a fascist group was brewing its power. She was uneducated and was based in a non-supportive and abusing family, which ultimately compelled her to use her youth and sexuality to support herself. Doris was a dreamer, but the patriarchal construct that enables violence and disdaining of the female gender crushes her. Her tale starts like that of a pretty girl in a world full of opportunities, but the narrative gets darker with every page and at the end she an echo of a woman who failed to fulfil the grounds of womanhood in a Nazi handbook. I’m a fan of Keun’s writing style after this one; I’ve become particularly fond of her witty yet humbling prose that precisely balances humour and sadness. Kathie von Ankum’s translation is engaging and kept me turning the pages quickly and perfectly captured the voice of a torn character like Doris. She was unlikeable no doubt, but she was the reality.

H**N

Didn't read it much, but quality is absolutely good

J**F

dated

L**H

Irmgard Keun was born in Berlin in 1905 and her first three novels (Gilgi, One of Us (1931), The Artificial Silk Girl (1933) and After Midnight (1937)) shone a light on a new generation of ordinary young women in 1920s and 1930s Germany who, along with the majority, had been crushed by the financial collapse of Weimar Germany. Doris, the narrator of The Artificial Silk Girl, is ambitious, somewhat naive, shrewd, dishonest, possibly with mental health issues, and keen to improve her prospects by using her looks and the stupidity of the men she meets. She is the quintessential material girl. Maximum gain for minimal effort. "I want to be at the top. With a white car and a bubble bath that smells of perfume, and everything just like in Paris" Irmgard Keun took inspiration from Anita Loos's Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and the debt is very obvious to anyone who has read both books. The narrative is written like a journal, albeit one without timescales and written in a stream of consciousness manner. It variously consists of her desperate attempts to become a theatrical star and/or find a suitable man to give her money and gifts. I had high hopes for The Artificial Silk Girl as I am fascinated by Berlin and Weimar Germany and, whilst it was interesting to read about experiences from a young woman's perspective some of which were presumably based on Irmgard Keun's own life, I was often confused and even bored by the style, and the repetitive nature of the plot. The Artificial Silk Girl was a bestseller and it's easy to see why given its frank and open discussion of female sexuality. It was predictably later banned by the Nazis.

M**N

You don’t have to know German to see that this book has been translated in a present-day chick-lit style. It’s full of gross anachronisms, things people simply did not say in 1931. The original novel might be good or might not, who can tell?

Trustpilot

1 month ago

3 weeks ago